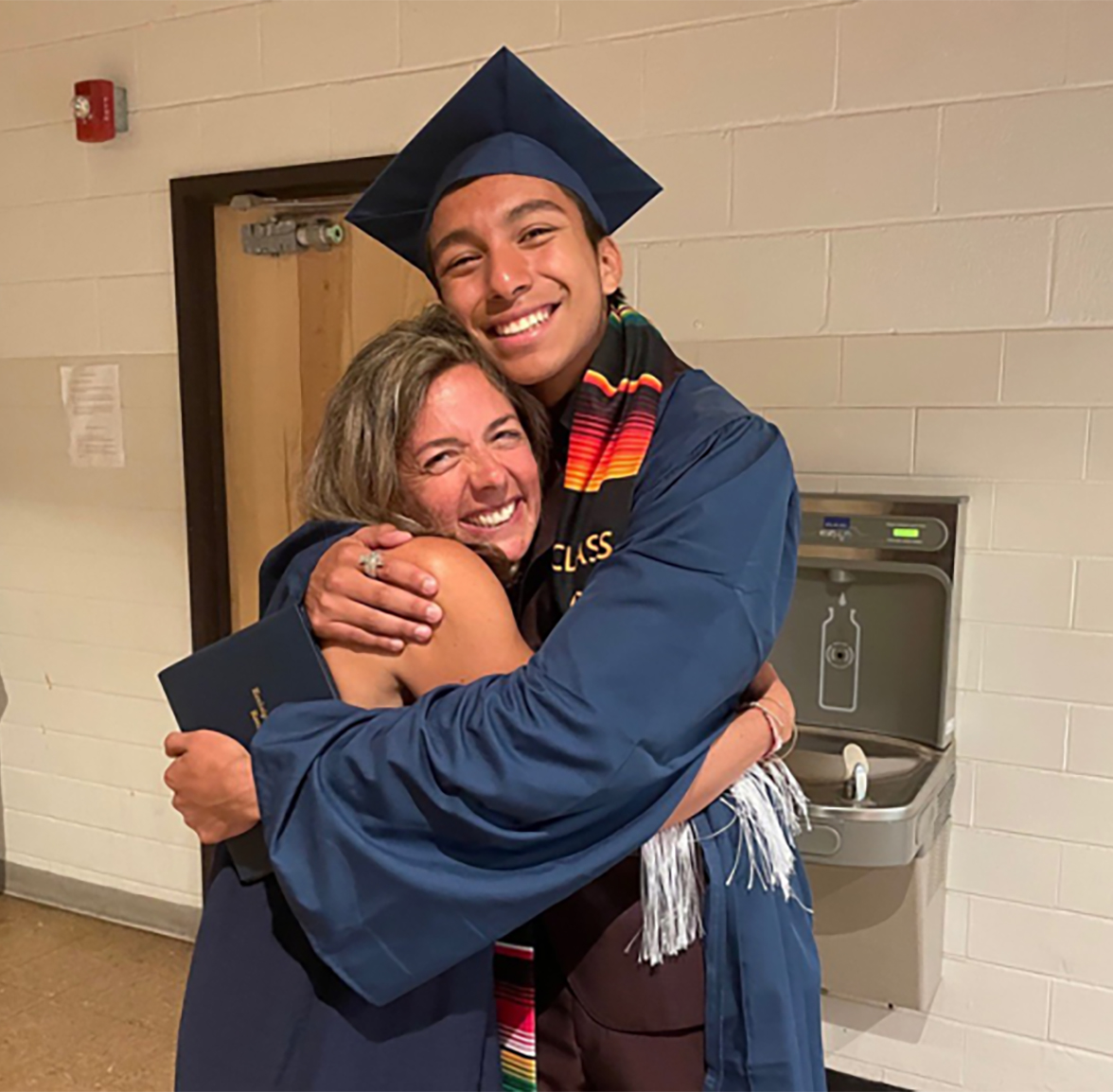

Pablo first met Mary Sell, an English Language Specialist, when his family moved to Randolph, Vermont from Mexico. For the next eight years, Sell worked closely with Pablo to ensure language was not a barrier to his education and coached him on advocating for himself at school. Interested in medicine, Pablo enrolled in Early College at Vermont Technical College while in high school but sometimes found it difficult to know how to access the same kind of support on a larger, less familiar campus.

“He had taken these steps toward college,” said Kara Merrill, school counselor at Randolph Union High School (RUHS), “but was having some ups and downs. I was worried.”

Recognizing that students like Pablo could use a little extra support, Merrill created an innovative new program that pairs college-bound seniors with an adult mentor of their choosing through their first year of college. Unsurprisingly, Pablo chose Sell, with whom he had a high degree of trust and familiarity. Now a first-year student at the University of Vermont, where he is thriving, Pablo credits Sell with helping to navigate the transition to university.

“There are people at UVM who can help with these things,” said Sell, “but they don’t know Pablo and he doesn’t know them. He has family support, but they haven’t navigated this system before.”

Pablo and seven of his peers from RUHS are the first to take part in the mentoring program, which is funded by the J. Warren & Lois McClure Foundation as part of an effort to make postsecondary education an easier choice for young Vermonters. Coming from a class of just 60, the eight students in the pilot represent 26 percent of college-bound seniors at RUHS.

The selected students—who are from low-income households, the first generation in their family to pursue college, on Individualized Education Plans (IEPs), or English Language Learners (ELL)—are asked to identify their own adult mentors from their high school community. The adults who accept commit to a one-year, paid mentoring relationship, formalizing expectations on both sides.

Student-led structure improves accountability

Bea is the first in her family to attend college. In and out of the public school system, she didn’t talk much about college with her family and, if she did, it was typically “a financial conversation that was very pessimistic.” Even after she was accepted at the University of Wisconsin-Madison to study architecture, it was a full month before she shared the news with her parents. “It was just something that was not asked about,” said Bea.

Her family, while proud of her, is not able to provide financial support or help Bea navigate the complex world of financial aid. “It’s a seriously intimidating topic and very isolating,” said Bea. “Your peers are doing all these things at the same time and you’re watching other people deal with those things and thinking: My situation doesn’t look like that.”

When asked if she would like to participate in the mentoring program, Bea immediately chose Merrill. “We’ve always gotten along,” she said. “I just felt this overwhelming sense of support from her.”

Mentors in the program are paid a $2,000 stipend funded through the McClure Foundation and asked to spend approximately one hour a week with their mentee throughout the first year of college. “The stipend does two things,” said Merrill. “It holds the mentor accountable and signals to everyone involved that there is value in the time these adults are providing. The students understand that and, I think, are more likely to reach out knowing it’s a contracted, as well as personal, relationship.”

The one-year duration of the program is also intentional. Most colleges and universities have excellent resources for students, but Merrill points out that first-year students who are experiencing all sorts of change may not know how to access those resources right away. “That’s where the mentor comes in, to bridge that gap between support from the high school community and finding their own network at college.”

“Some get there and don’t make it. Why?”

According to a 2022 report by the New England Secondary School Consortium, college persistence (defined by enrollment in a second year) in the region generally hovers just above 80 percent. Economically disadvantaged students, however, persist in college at 68 percent (2020). The rate of persistence for English Learners and students with disabilities has declined over the past decade and are now both at 66 percent (2020).

“The high school community works so hard to get kids ready for college,” said Merrill, who is both a mentor and the program coordinator. “But then some get there and don’t make it. Why?”

For Owen, a RUHS graduate currently in his first year at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, navigating registration, housing, and financial aid with dyslexia, ADHD, and social anxiety was overwhelming. Disbursement of his scholarships required a final schedule on school letterhead, but the school required full payment before registering and scheduling classes. “I made so many phone calls,” he said. “Each telling me it’s the other side’s problem and saying there is nothing they can do.” He ended up on low priority for both class registration and housing.

His mentor, Heidi Schwartz, a special educator at RUHS, established regular check-ins where they talked about everything from paying bills to getting outside for fresh air. “For a student like Owen, who I know has everything he needs to be successful in college, it’s just that little extra bit of wrap-around support.”

“I’m a 2E student, meaning twice exceptional,” said Owen, “which can be hard to explain to people. Having someone to go back to when that is an issue has been incredibly helpful when dealing with professors. Having that backing has made a massive difference.”

Navigating life away from home

Annabelle, who is studying education at Vermont State University’s Castleton campus, credits her mentor, Chancity Young, a teacher at the Randolph Technical Career Center, with helping her get through her first semester. The first in her family to attend college, she found the adjustment to life away from home difficult.

“I’ve lived in Randolph my whole life,” she said, “so moving away was a lot.”

Prone to staying isolated in her dorm room or going home over the weekends, Young encouraged Annabelle to try one new thing on campus each week. She went to a few sporting events, attended a Build-a-Bear workshop, and started going to the student center just to people-watch.

“I started out just sitting by myself but now I have this great group of friends that I sit with and we all do our school work together,” said Annabelle. “I put more things up in my room, because it used to be just a blank white wall, to make it feel a little more like home for the next four months.”

Like Young, Annabelle plans to become a teacher. “Chancity helped me so much to get to where I felt comfortable to leave and go to college,” said Annabelle. “I knew I wanted to go into education since middle school. I just didn’t know what direction I wanted to take.”

Ripple effects and lessons learned

“Big picture, my dream is for more kids to access college successfully,” said Merrill, “and it shouldn’t depend on whether their parents know how to navigate this process. They have to feel someone has their back. Otherwise, they can feel thrown to the wolves.”

Even as a seasoned school counselor who attended a four-year liberal arts college, Merrill is learning alongside the students through the pilot. “It is so complicated for kids to transition to college,” she said. “I’ve really been reflecting on that and thinking about how we can support them differently.”

One big area of learning has been the gap between when bills are due and scholarship money is disbursed. More than a few of the students in the pilot expressed how scary it was to have thousands of dollars’ worth of bills to pay and not know when the money would come.

Merrill is considering an orientation next summer for mentors and mentees that would set expectations early on. “We can say to them now, ‘Your scholarship money is not going to be there when you arrive. Take a deep breath. It’s going to take a few weeks, but it’s going to work out.’” She hopes that by bringing the students together early on, she can also help them feel less isolated.

Merrill was surprised to learn that first-year students are making housing decisions for the following year in their first few months at school. Bea jumped through all the hoops to find an apartment with her friends, doing careful math on how much she could earn as a barista to supplement her rent. At the eleventh hour she discovered that, although she is 18, she needed a parent to co-sign a lease. “It all went sideways,” she said. “So, I’m living in the dorm again next year.”

There was not much Merrill could do in that situation, other than listen, validate, and help her think about the positives. And bring that learning to next year’s mentees.

Merrill hopes the pilot will provide a roadmap for the program to be adopted at other schools. “The mentor is kind of a bridge between high school and college, where kids are kind of learning how to be on their own for the first time. It’s one way we start to close the gap on college persistence.”

“It really matters,” said Schwartz. “I’m so excited about this program for kids who, with just that little bit of extra support, can go on to show the world how amazing they are.”

About the J. Warren & Lois McClure Foundation

The McClure Foundation is an affiliate of the Vermont Community Foundation that works to close opportunity gaps in the state by strengthening college and career training pathways to Vermont’s most promising jobs. mcclurevt.org

Philanthropy can help.

Vermont has among the most expensive in-state tuition nationally and fewer than half of high school graduates enroll in college. The good news: when we make college and career training affordable and accessible, Vermonters enroll.